A Smart Home in A Dumb Body

-

A solo show at Hansen House, Jerusalem

Curator Vardit Gross

Year 2023

The city is closing in on us. The buildings keep getting taller, making the sky smaller, contracting the lungs. Even inside the apartment it becomes increasingly difficult to breathe. Technology pulls us upwards, towards the future, but through the windows of the house one may sense an apocalyptic present, the air of an approaching disaster.

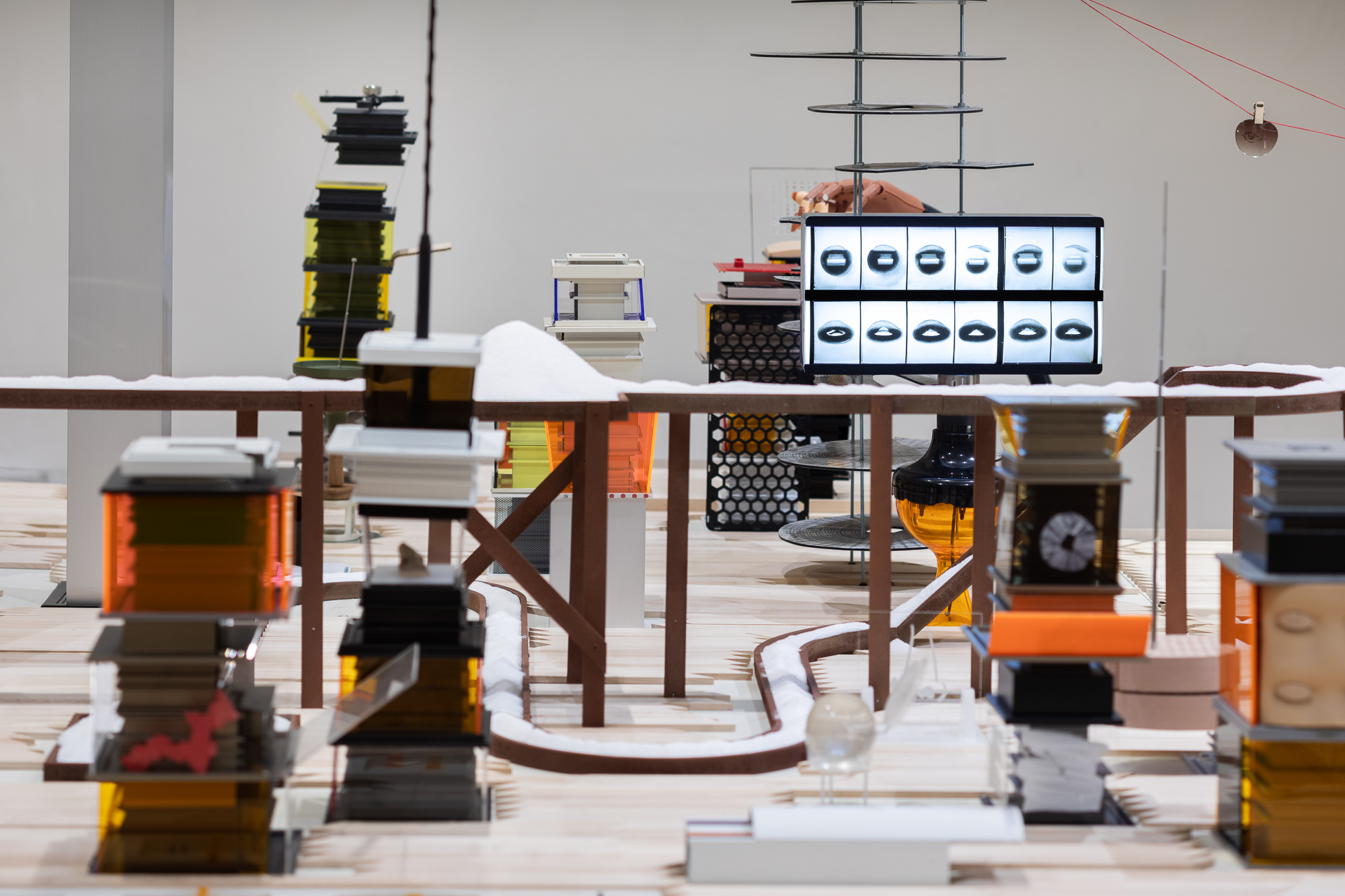

In the one-bedroom apartment built inside the gallery at Hansen House, Guy Goldstein explores the relationship between the city and society, as well as the political, social, and material processes that shape it. His starting point is Hansen’s permanent display, which recounts the history of the leper shelter. In dialogue with the display, he builds a contemporary cluster of rooms in the gallery space, which also engages with loss and loneliness.

In the past, lepers were isolated in the outskirts of the city, and the shelter served them as a last stop—a place which they never left, while their bodies were gradually decomposing. The body in the exhibition “Smart Home in a Dumb Body” is also gradually disintegrating, until it is assimilated into the city surrounding it. Through the eyes of the high rises, the ears of the guard towers, even standing in the very guts of this city—you still feel alone. It is an architectural entity which dictates consciousness, eliciting cultural pessimism regarding the effect of progress on the future of mankind and the constantly growing technological alienation.

In the 1970s, in his laboratory in Maryland, ethologist John B. Calhoun overcrowded mice, and proved that an overpopulated society, even if its material needs were met, would collapse due to psychological stress. The rodents, which started attacking one another to the point of cannibalism, were unable to return to a harmonious social life even after their conditions were improved.

In the social and political experiment taking place in recent decades in our big, crowded cities, progress offers us alternatives, such as limiting and controlling the natural population growth and replacing the destructive urge with consumerism. It is unclear, however, whether these are enough to save us, or whether modernity, with the supervision and policing it brings, is at the very root of the problem.

Goldstein reconsiders the living conditions in an anonymous urban space, devoid of place and time, and the changes in the social, political, climatic, and technological order that has brought us to this place as individuals and as a society. In a large-scale surrealist installation, he constructs a world both familiar and unknown. The objects, the rooms of the apartment, the pieces of furniture and their use are familiar, but their existence and function are constantly disrupted: the digestive system is laid on a dining table made of an ironing board; heaps of hair metamorphose into a coconut; LED signs serve as a bed; the toilet is flooded with glass balls.

The exhibition moves back and forth in time and space—from gloomy interbellum Europe to a future dystopian city; from the skyscrapers that fill the city, to the tiniest details of the apartments that make them up. Concurrently, Goldstein points at the breakdown of the known, moral, and functional order, and the disintegration of the home—the one surrounding us outside the gallery and the one installed in it: from clashing ideologies, through a cluster of furniture and body parts, to mounds of sea salt that attempt to preserve the good old order, which seems lost.